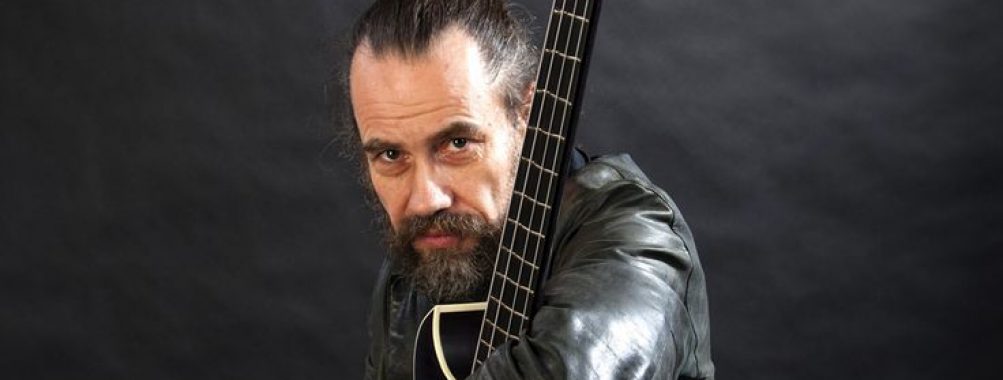

Jonas Hellborg A Candid Conversation

Over the last 30 years, Jonas Hellborg has simultaneously defied and defined what it means to be an electric bass player. In the 21st century, he is doing more of the same. As one of the most iconoclastic musicians experimenting with the bottom frequencies, Hellborg has seemingly never been at a loss for ideas or direction.

From his new approach to the bass (aside from Spinal Tap, who else had the balls to play a double-neck bass?) with John McLaughlin’s third Mahavishnu Orchestra, to his groundbreaking work with virtuosos Shawn Lane and Jeff Sipe, through his current focus with drumming maestros Selvaganesh, Ranjit Barot and freak guitarist Mattias IA Eklundh, Hellborg has always found ways to innovate within the confines of composition, improvisation and technique. But try to ask him where he is consciously going in his journey and you are likely to get an answer that is at once hazy yet steadfast. He struggles to define what the music is, but is confident in his approach, which is, at the moment, centered on his guitar trio.

Due to editorial guidelines the full interview wasn’t published in the May issue of Performer Magazine Abstact Logix now presents Jonas’ full perspective from January 2010.

On Current Projects: I’m just dealing with a bunch of different musicians. It’s all a network of people. Of course the center core of the Indian music thing for me is Selvaganesh, who I’ve been working with for ten or 20 years.

On the Genesis of Indo-fusion Projects: I played with John Mclaughlin, was a huge fan of Shakti, and the person I admired most in Shakti was Vikku. And I never got to meet him when I was playing with John. I was at a Frankfurt music trade show about 15 years ago and I heard about Vikku’s son. I was really excited and I wanted to meet him and hook it up and he wanted to meet me also, but we could never get it together. I think it was like 1991 or something like that I came back to Paris where I was living at the time…it must have been 1995 or ‘96. Somebody calls me up and says Zakir is playing today and Selvaganesh is playing with him, so I went to the gig and we met after the gig in Paris and from then on we started playing together. Selvaganesh is the center figure in my whole connection with India and Indian music and through him I met Ranjit Barot and I really love how Ranjit plays the drums because he is a kit drummer and he knows all the classical Indian stuff but isn’t trying to make it sound Indian. He just uses it in kind of jazz or fusion kind of language. So if you just listen to it casually you wouldn’t even know it is Indian stuff, it would just sound like this intricate incredible stuff. But it being Indian, it makes me able to approach it that way or to understand it that way and integrate with it. So what comes out is not all Indian sounding but it elevates the jazz language to a much higher level.

On Mattias Eklundh: After Shawn [Lane] the only guitarist who interested me was Mattias Eklundh because he has also an incredible capacity and a totally different approach to how he’s doing stuff. And a vast knowledge of music.

What unites them is that they both know all music. With Shawn, I could play classical music, and with Mattias I can play classical music. With Shawn I could play Indian music, with Mattias I can play Indian music. With Shawn I could play rock n’ roll music, with Mattias I can play rock n’ roll music. It’s the same sort of relationship which covers all the musical territories necessary. And my instrument, my ensemble is the guitar trio and it has been since I was a kid. It’s my natural environment in which to play music. This is just a continuation of that work. We tried the Art Metal thing because we wanted more architectural kind of project so we tried to do that. But when it comes to just playing, just blowing, that environment is the easiest for me to handle, to deal with, so we went back to the trio format.

The Art Metal thing was much more about structure, about compositions. This is about improvisation. It’s a whole different thing.

He covers music on a level on which I am comfortable with. If I ask about string quartets to understand what that is have heard that and be familiar with that. I can’t start by explaining who Bela Bartok was if I want to go that stylistic direction or approach. And if I say rock I can’t start by explaining that approach or what that is. I can’t educate people who I am playing with. I need someone to come to the table and give me something. I don’t want to play with my students. I want people who can challenge me and elevate me to the next level.

I do not want to revisit places I’ve already been.

On Composition: At the heart of this is me; it’s what I do and what I’m comfortable with. I play bass. I will continue to play bass. I’m not going to switch to tuba all of a sudden. I know how to deal with the trio. It’s like you say you write for string quartet as an instrument as you write for piano as an instrument. I write for guitar trio as an instrument in the same way. We’re not doing the same thing we did with Shawn. There is a whole new set of ideas and knowledge that has come at this point in my life. My understanding of Indian music is deeper, my understanding of life is deeper, my understanding of classical music is deeper. Everything has gone to another level. [I’m] not taking anything away from what I did with Shawn which was great, but this is another time and another approach and has another depth to it.

I look at it like this. For some people they could look at something as a certain style of music. For me that is not valid because it’s basically based on the instrumentation always. If you hear a certain piece of music played by a string quartet they will say classical music. If you give the same music to Megadeth it will be heavy metal. But it might be the same notes being played. So what is the style? Is it the instrumentation? So I can’t really discuss style or stylistics. To me, that’s fashion. And I’m not dealing with fashion. I’m dealing with music. The parameters and knowledge and human implications of what music and musical sources are. I learn with all types of interaction I have with other human beings and that comes out in my music. It’s about substance, not about style. It’s about content.

If I meet somebody, I want to interact, discuss, synergize and find something I didn’t know before. I’m not here to lecture anybody or tell anybody about life. I’m here to learn, not to teach. I’m not going to tell anybody what anything is. I’m not going to try to push my answers to the questions of life down anybody’s throat. I’m just exploring, experiencing, learning and studying. And that’s what these meetings are. It’s not about telling anybody how great I am. If somebody gets something out of what I do, I’m very happy, but I don’t see it like I invented anything or created anything, because whatever comes through me, I’m just a mirror reflecting the light that has already come down through the centuries. It’s coming from this mirror to that mirror and it’s just reflecting. It’s just a different angle.

On Selvaganesh / Carnatic Rhythm: Selvaganesh and I have the duets. And we’ve never done a duet album yet. We’re working on it. That includes me developing my bass playing to a new level and a new standard. I’m working very hard on that.

Selvaganesh understands western music very well and western drumming. He can play a groove like a motherfucker. He can really hit it. We westerners think of pulse and then stuff that falls within the pulse beat. Indian rhythms consist of musical phrases that make up the totality of a whole. And it’s not about the bar. It’s about the whole periodic movement that might be repeated or not be repeated.

On Jazz: If you just play rehashed Charlie Parker or Coltrane licks, what’s the bloody point? If you are going to do it, write some new chord changes and go somewhere else. Don’t play fucking “Stella by Starlight.” That’s not now. It has nothing to do with now. You have to understand harmony, tonality, and of course you have to study that stuff, but jazz or bebop is just one expression that is very bound into certain time aspects and social situations that aren’t valid anymore. Here we have a song that is not normally a very intelligent harmonic composition anyway, it’s just the bloody same ii-V progression in eternity over and over again. As soon as you learn to play over ii-V-I progression, you can put those building blocks and go doopie doopie doopie doopie forever. What’s the fucking point? This doesn’t make any sense. So you have to be smarter than that. If you go back in time and study Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and study harmony for real. Then all of that (jazz) harmony is rubbish—it’s useless. Take something out of that history, make it modern, make it today, and do something that hasn’t been done. Then wow, great. Modern Jazz pedagogy is totally fucked. I can explain all that stuff on one page. All that stuff you go to Berklee for four years to learn I can explain on one page. But I don’t because everybody should figure it out for themselves because there’s nothing to it. It’s empty.

Bebop think bebop is tradition and I would say no, it’s not. Bebop comes out of the crossroads between western classical music and the black tradition which I would say is an African tradition, which has to do with gospel which is a cross between European and African music, going back which is traceable back to African music. And so there’s that tradition of course. But even Duke Ellington studied western classical music to make his compositions. If you are really getting into that, his compositions and his arrangements, there you go. Then you have something worthwhile to study. But study it, and OK, play it for educational purposes, but you don’t have to recreate it.

On Expression: I think all expressions are valid. Having said all that, I can totally contradict myself by saying whatever you feel to express yourself is who you are and what you should do. So if you feel very strongly that you should play doopie doopie doop then that’s who you are and I cannot criticize that. I am not here to tell anybody what they should do.

On Style: Wayne Shorter is the god. He’s amazing. Because it’s music. It’s beyond stylistic. And Keith Jarrett does everything I am criticizing. He’s playing “Autumn Leaves” and whatever, and what he’s doing is unbelievable. It’s amazing. But it’s not doopie doopie doop. When he plays it’s composition. There is intelligence. There is continuity. There is cross reference. He doesn’t just play a bunch of phrases stacked on each other. He starts and from the point where he starts to where he stops playing. There is a thread. He builds a house. He builds a cathedral. It is improvisation on the level of the great Indian masters. That’s what they do. It’s not, “Now I play this lick, then I play that lick, then I play that lick.” No. It’s music created in the mind in time, in consciousness, in continuity.

If you give up formulated music, you can actually attract normal people. Because when you have a click of people, let’s say you have the fusion click. Then you start to set rules for what is fusion. If you have the jazz click, you start to set rules for what is jazz. And if you just let that go and you actually deal with human, general human tastes in music, what actually moves you and you get away from the whole concept of, “Is it stylistically this music or that music?” then you will actually attract people who are not in your field. Keith Jarrett, case in point. People will not listen to [imitates traditional jazz]. But they will listen to Keith Jarrett because he’s making music. What he does goes beyond styles. You can take someone like Stevie Wonder. He’s an R&B guy, but everybody loves Stevie Wonder. Why? Because he goes beyond that. And whatever level you are on, if you actually don’t cut any kind of musical parameter or resource of your world, just because you are this or that, which is what stylistic ideas do, they confine you. Then you will deal with music as it is. It’s just like food. They talk about fusion food. I don’t like the term, but the fact is I have Indian spices in my pantry. So when I make an omelette, I get something out and I put it in there and it tastes good.

If you decide to be in a small neighborhood and stay there all your life, that’s what you do, and that’s fine. That’s just another choice. But if you live in the modern world, the global world, you are encountering all these things. You just deal with it. But do whatever you like. You take it and you use it. Whatever is in your culture. But they key concept for me is not to confine yourself just because it’s supposed to be that way.

On Meaning In Music: In order to be a fulfilled human being…I don’t want to use terms like spiritual because it kind of gets out of the subject. But in order to function as a human being, you have to be able to focus. You have to be able to center. Some people are into religion. They pray or they meditate or they do this and that. Music is such a thing. It’s a discipline and you use it for the purpose of focusing your mental, your spiritual activity in one direction and become whole. And as you do that you will get more and more capacity as a musician. But if you can express what you need to express with just a very limited vocabulary, you can still do that. It’s not about the vocabulary. It’s not about how many words you can use; it’s about what you can say.

I don’t want people to admire me, and I don’t want to admire people. We are all the same. We all have basically the same capacity. I admire Gandhi. When you think about what Gandhi did it’s unbelievable. Everybody can learn a scale and everybody can practice forever, but it’s the other thing. But really, it’s a quest for truth. It’s sort of encapsulated in what Thelonious Monk said: “The true definition of a genius is one who is most like himself.” It starts and ends there. And when you are really in tune with yourself—and this is where the discipline comes in, and you really express yourself truthfully and powerfully, then people will say, “Oh wow. That’s amazing.” And it doesn’t matter if you do with two notes or a fugue or a really intricate rag, or whatever it is. It’s the same thing. It’s the spirit. When are you open and clear and innocent like a child, that’s when it really hits you. And that’s why somebody like Wayne is so powerful. Because he really does that.

Buy

Itunes-note Amazon Bandcamp