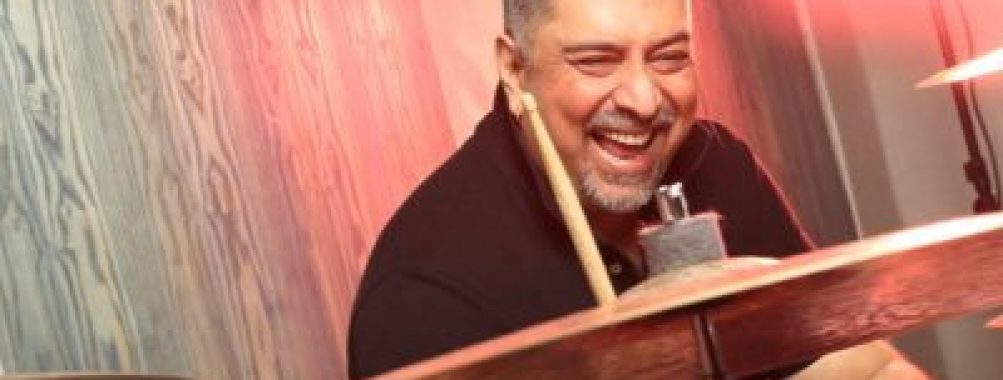

Drummer Ranjit Barot Interview

Buy

Itunes-note

Amazon

Bandcamp

DUALITY ON THE DRUMS

THE FUTURE OF MUSIC DEPENDS ON ALL OUR CULTURES INTEGRATING.

Ranjit Barot is India’s premiere drummer on the drum kit…and if you live outside of India chances are you probably wouldn’t know that. But with the release of “Floating Point” , John McLaughlin’s studio CD on Abstract Logix, that is about to change.

Recorded in Chennai, India, “Floating Point” features what McLaughlin calls some of the “young lions” of India’s music scene. A wonderful amalgam of “raga meets fusion,” “Floating Point” will undoubtedly expose these amazing Indian musicians to a wider western audience. And while there are many musical highlights on the CD, it is the drumming of Ranjit Barot that is truly the standout performance.

Ranjit infuses his western influenced chops with his Indian soul. He creates rhythms that are intricate and unpredictable; yet they groove ferociously and swing effortlessly. He makes odd-time signatures seem as natural as breathing. Ranjit plays with limitless energy, endless imagination, and total abandon. McLaughlin calls him “One of the leading edges of drumming.”

Ranjit Barot is also one of India’s top music producers, and an accomplished composer and arranger. He has written numerous films scores and performed with some of India’s best musicians. Information on Ranjit’s early career and his film work are at www.ranjitbarot.com and www.heritagejazz.com/ranjitbarot.html.

In addition to music and drumming, Ranjit is very passionate about life and his family. That passion was very evident during our phone conversation from his home in Bombay, India. Throw in a sense of humor, and Ranjit is engaging, insightful, and a sheer delight to talk to.

During the “Floating Point” sessions, McLaughlin would jokingly say “You got it, or you don’t got it!” to the musicians after working with them on song arrangements .

Ranjit Barot – you got it!

Rod: Did you play any instruments before the drums?

Ranjit: Well, I come from a classical family in as much that my mother is a classical dancer. She’s the exponent of a form of Indian classical dance called Kathak, which is North Indian in its origin. I grew up with that. It’s funny, I really didn’t think I’d play music until I was like maybe 14 or 15. Somebody in school said, “Hey, we need a drummer.” I said, “Alright, I’ll give it a shot.” And I played. And I played how I thought you should play. But, my life changed; my life changed after that for sure.

So I didn’t really play any instruments before that. The drum set was my first sort of initiation as a performing musician. I played in a lot of progressive rock bands, and if the guitar player went out of the room I’d pick it up and I’d start messin’ about. I taught myself how to play a little bit. But my primary instrument was drum set.

Rod: You just had a natural affinity for it?

Ranjit: Yeah, it’s something. I wasn’t really like the quickest learner. I kind of plodded through. I mean, I had good time and I think I had good taste – so I could disguise. Even if played really badly, I kind of made sure nobody else found out [chuckles]. I didn’t really know how all the pieces worked. You have to understand when I was 14 in India, we had no television; there was nothing, man. It was hard to kind of put it together. Most of the guys who played ended up playing in lounges in hotels. So it wasn’t a career option for a lot of kids. I’d have to listen to records and try to put it together to see how the hands and the feet worked. So it came slowly, but eventually it came.

I had this “thing.” I felt this instrument. If I listened to a James Brown record, I could feel that backbeat. I knew the emotions behind that rim shot; it was not alien to me. And I said, “I want to be a drum set player.” I think that’s the beauty about music. Alla Rakhaji had an American student, who is no longer with us, but he played tabla. I mean he played like very few Indians ever played. So I think music belongs to all of us. And it’s possible to feel this culture that’s so far away.

Here’s an interesting thing. I knew very early in my life – I don’t know if it was like a point I had to prove – I knew that the drum set was a “western” instrument, so to speak; that it came from the west. And I wanted to play the drum set. I didn’t want to transpose Indian stuff on it, and I didn’t want to do mouth percussion, and I didn’t want to play tablas so I could dazzle western audiences with something they didn’t know. Unless you are Zakir bhai, then it doesn’t matter where the instrument or the audience is from, it just blows it away. I wanted to play their instrument and be accepted as a drummer; as a drum set player.

Rod: What types of music were you listening to around that time?

Ranjit: When I was growing up in England, The Beatles were getting big. I kind of slowly got into them. All the popular TV stuff – The Monkees, Spiderman, Batman – we’d be exposed to all those themes.

But you know something: I kind of got into the Mahavishnu Orchestra before I got into the pop-rock stuff. It’s like I got into The Beatles later. I wasn’t so interested in the whole pop-rock thing. And when I came to India I started messin’ with music. And the first time somebody played me “Birds Of Fire” and I said, “Forget that other stuff, this is how music should sound! I mean really, I’ve been messing around ’til now. This is IT, man!”

Rod: Did you feel you had to reconcile between the music you were listening to and the music that was part of your classical background?

Ranjit: No, no. The interesting thing about my childhood was that even when I was living in England, vacations would be back in India. I had this really Cockney accent. One minute I’m playing soccer in a park in London, and then I’m in India flying kites and I’m messin’ with the local kids. Winter was really cold, so my mother would like to be here in India. It was this incredible duality. And I seemed to kind of fit in where ever I was. So nothing about any of the cultures actually threw me. It came quite naturally to me.

And then once I started playing music, I think in a subconscious way, I kind of brought everything that I’d been exposed to through my mother. Because of my mother I got to meet all the great guys. Ustad Zakir Hussain’s father Alla Rakha would come to the house. And great sitar players like Vilayat Khan. I got to meet all these guys and get blessed just being in the same room as them.

So it was an incredible childhood for me.

Rod: Did you take lessons from the Indian masters when they visited your home?

Ranjit: It was sort of informal. I was really young man; like 12, 13, 14. Alla Rakhaji would come over and he would get me into a room and he’d say, “Okay, sit down.” My mother used to have a lot of jam sessions at home. Great jams where musicians would come, food would be cooked; they would play, she would dance. It was quite a buzzing scene.

It was great for me, I got all this exposure. Alla Rakhaji would sometimes get bored and he’d say, “Let’s go in the room.” And he’d just start reciting these patterns. I’d just sit there and – I was too young to really deconstruct all of it. But I knew that some shit was going down, man. I knew this was some heavy stuff. I just let it wash over me.

Rod: When I was preparing for this interview, the thing that blew me away was when I read that you’ve never have any formal training on the drum set!

Ranjit: No. I’ve never learned the drum set, or anything else.

Rod: Woooow.

Ranjit: Yeah [chuckles]. Well, having said that, I think we all create our own academy. I think we all create our own training ground. I mean, I copped so much stuff from all the drummers that I listened to. I had to rip them off initially to understand how the drum set worked before I could unlearn it and find my own style. I tried to play like Billy Cobham and I tried to play like – the first time I heard Elvin Jones I was like, “Man, what is THIS?” That was a whole other thing; and so linear and incredible.

And then later on, Jack DeJohnette. All the Weather Report drummers: Alphonse Mouzon – all these great drummers. And I would try and see how – try and rip them up just to understand that this is what your hands and legs can do. And then put it aside ’cuz they’ve already said that. There’s no point in me trying to sound like that.

Rod: You sound like a hard-core fusion fan.

Ranjit: Aww, man, of course! And I’m telling you, I got into all of that stuff before I went back and then revisited everything that was happening in the rock scene in the ’70s. The whole progressive thing just got me going.

Rod: I know what you mean. I was into Hendrix and the rock thing, but when I saw John McLaughlin and the Mahavishnu Orchestra, there was just nothing else after that. It was like some big revelation had hit.

Ranjit: That’s about how it was for me. When I heard Cobham play – and I tell you this in retrospect: I’m a fan of every drummer on this planet. I think there are so many, so many great drummers out there that it’s hard to create a list. But Cobham is a pioneer, for sure. Cobham is the closest I’ve heard a drummer playing with an Indian soul. He had the whole “speech” thing down.

Rod: I read where Billy said his approach in the MO was based on he thought the MO needed a percussionist. So he decided to be the drummer and the percussionist.

Ranjit: The whole tradition of mouth percussion that comes from India hasn’t really yet been mirrored strongly on the western instrument. You hear kids doing beat box, and you hear things like that. And I think in a contemporary vein, yeah, that’s vocal percussion; but not as deep as what Carnatic percussion and North Indian percussion does.

But Cobham, when he played, I could hear him talk. His snare drum, that’s the heart of his language. He really had this speech happening on the kit.

That’s what stopped me in my tracks. Because I’d been listening to tabla players, and I said, “Hold on. This guy, he understands. He understands where this whole thing is coming from.” So he was probably the first big influence. And I just love everything he’s done, man.

Rod: Speaking of languages, when did you learn konnokol?

Ranjit: I toured Europe with kind of a jazz-rock band from here and there were a lot of south Indian percussionists. I started informally learning from them, because I had to play a lot of that stuff on stage. We’d travel by bus through Europe and I’d sit and take lessons from the mridangam player in the band. I have a friend – very, very close brother of mine is a mridangam player, Sridhar Parthasarty – who now I formally learn from.

Within the last 5-10 years was when I started actually going back to my Indian roots rhythmically: finding a meeting point for what I can do on the drum set and phrase and syncopate with some kind of Indian soul; and not take away from the language of the drum set. I take an Indian rhythm and transpose it on the drum set; you understand what I’m saying? But to take a rhythmic pattern and then play it on the drum set [sings] “da-da-da-da” is too literal. I want my playing to be the duality that I am. I am very, very Indian. I dream in English. And that’s who we are. And I want to play like that.

Rod: I think it’s fair to say that you’re a pioneer as well, playing the kit drum in India.

Ranjit: In some way, yeah. When I started playing there were a couple of guys who played really nice and who I’d sneak out to go and listen to gigs. There was not a whole lot happening. There were a bunch of rock bands, but nothing really that heavy. And because I got into Mahavishnu and Return To Forever before I started playing pop-rock, I started gigging.

I dropped out of college, and my mother said, “Listen, if this is what you want to do, fine. But I need to see you making money. I need to see you supporting yourself. Because otherwise, get your ass back in college.”

So I took any gig that came, you know. I was lucky that I was this sort of this new kid in town and guys wanted to play with me. And I got to play with two really good bands. In fact, in one of the bands I played in I replaced Trilok Gurtu; ’cuz Trilok left and I joined the band. It was a progressive rock band, and it was one of the few bands that was really playing in odd-time signatures. We had a song in 10-1/2, and for that time, it was kind of a little whacked-out [chuckles]. You go play a college festival, and the last band has just played a Rolling Stones cover; and we’re on stage playing in 7 and 10-1/2.

But you know, it was an interesting time. Nobody had told people that you can’t groove to a 5. There was no television to tell you that four-on-the-floor is the only way you could have time. So we had kids bopping to anything we played. Even if I played backbeat and I played rock’n’roll, I played it like if Lenny White was to play a backbeat.

So broad is simple. I always told musicians that it’s more of an eastern philosophy. But all of the great – I mean, look at Vinnie Colaiuta, man. What a great drummer. And he can groove…

Rod: Oh yeah, killer.

Ranjit: …and he plays a groove, I mean, that’s a groove . And I think that’s because he has so much in reserve. It’s like being a 10,000 watt amplifier and saying, “Oh well, I’m just going to use 50 watts today.” That 50 watts is so sweet and it’s so clean . So full of conviction. And it’s got so much in reserve, that it’s pure. I think even if you’re a session player, or whatever, I think you should be able to play a lot more in reserve and not maxed out.

So I guess what I’m trying to say is that when people came and heard me playing in tavil bands or heard me playing in a rock’n’roll band they heard a groove. And because I could play a lot more, it kind of swung and sizzled in a way. And it’s great because it made a lot of kids get up and play drums and join bands. I have a bunch of kids who come to the studio; they kind of learn from me, and I’m happy to teach what I know.

Rod: I read where you said that in the ’80s, it was hard to make a living as a drummer.

Ranjit: It was. 1986, I think, is when the electronic revolution hit India; and I got replaced by basically a drum machine. It was heavy, because I was not making any money; and it was kind of scary for a bit. I got a break working in a studio. This piano player, who’s also on “Floating Point” , Louiz Banks – an old friend of mine – he gave me a break in the studio. I wanted to leave. I said, “Well, I’m gonna go to America. At least there are still drummers there.” I didn’t really know whether they needed drummers, I just felt that any place besides Bombay would be okay.

And Louiz said, “No, no, no, no. I can’t have you leaving ’cuz you’re around here and the only drummer really that can play the way we want. Grab your kit, come to the studio, and I’ll get you a gig working on advertising scores and stuff.” So I went. And that’s how I started working in the studio; making a living doing sessions, programming drums, and producing a little bit. Then I kind of branched out on my own, and it sort of progressed from there.

Rod: What eventually happened with the drums?

Ranjit: I wasn’t playing so much drum set for awhile, I was doing all this production stuff. One day Zakir Hussain just threw me in the deep end. He said, “Well, you know there’s a gig here. I‘m playing with L. Shankar; come in and sit in.” I was kind of nervous ’cuz – you know how it is? It’s like Narada Michael Walden. You spend ten years producing Mariah Carey, and your chops are not up. And these cats will eat you up, man. They won’t hesitate letting you know how out of shape you are, you know. And I think that day when I played with Zakir – yeah, I mean, I played okay. But I knew. And I said, “I’m never gonna let this happen again.”

Rod: So you had to do some woodshedding to get your chops back up?

Ranjit: Gotta keep ’shedding, keep ’shedding. And when I got the call to play with John [McLaughlin] it was just like, it was absolutely…he’s my hero, man!

Rod: Do you have a favorite John period?

Ranjit: I think everything – I love everything he’s done. Everything from the Mahavishnu Orchestra; Lifetime with Tony Williams and Larry Young. Then his whole flamenco period. Shakti, of course, because we grew up listening to Zakir bhai. So when Shakti came on the scene, we were blown away, man, you know. And of course, that whole flamenco period with “Belo Horizonte” and those albums. And what he did with Trilok.

John’s a – he’s John McLaughlin, man. Everything he does is steeped in great taste and sensibility. And he understands all these cultures; he’s not messin’ around. He’s played flamenco with respect and humility; and he understood that music.

Same with Indian music. He can take – well his connection with India is so strong that because he’s such a master with all the western harmonic stuff, he’s able to look at Indian music and integrate it with what he knows so seamlessly. But he’s scary with time too, man! He’s like a drummer, really. There’s nothing you can throw at him that he can’t…incredible, man. Incredible. John’s such a visionary. Awww man, he’s a master.

Rod: Had you met John before the “Floating Point” sessions?

Ranjit: Yeah. We met once, really briefly, in Europe with Trilok. Trilok was playing with John and Kai Eckhardt. I was in Holland at the time and I knew they were playing the North Sea Festival. So I met John briefly backstage; it really wasn’t a very long meeting. And then, in Bombay for Zakir bhai’s memorial for his father. The third time I met him, we jammed onstage.

It’s quite an interesting episode. You know Zakir bhai does this 3rd of February memorial to his father. Steve Smith has come; Terry Bozzio has come; Vinnie was supposed to come, but I think his mother was very ill. Ah, every young drummer – oh, Antonio Sanchez was here. And the year I got to jam with John, Eric Harland, the young drummer who Zakir bhai and Charles Lloyd play with was featured.

Zakir bhai features a drummer every year. The first drum set player to be featured at one of the festivals was me; and then subsequently every year he gets someone to play the drum set. The festival starts with sun rise and it finishes like at 10:30, 11:00 at night. And in the evening there’s this sort of jam: all the musicians who participated during the day come onstage and basically jam. So, Eric Harland was there and he did a solo in the day time.

John landed up with the guitar; he had done the morning session. When I knew John was onstage I said, “Wow, man. I get to play with John McLaughlin. This is fun.” John and I started, and I think he heard something in my playing, man. He just turned towards me, and that’s it; the next 10-15 minutes we just connected.

And what happened was, during the jam Zakir bhai – we look at Zakir bhai – conducts the jam. So he told me, “Why don’t you tone down and let John play with Eric?” So I kinda backed out a bit so that Eric could kick in and start trading with John. And as I started kind of winding down, John just shouted – he just looked at me – he says, “You can’t stop now, man! We’re just getting started! You can’t stop now! Forget about the other guys. Keep playing!” So I begged Zakir bhai’s forgiveness and I went for it. ’Cuz John’s my hero, man. I mean to play with him is…

I finished the jam with him, and I remember I was – two days after that I was sitting having my morning chai with my wife Maya and I said, “I played with John. That’s like…I played with John McLaughlin. That is something, man.” And as I sat there – it was really like a movie – my phone rang and it said “John McLaughlin.” We had traded numbers that evening. I said, “Hello.” John just called and he said, “I wanted to tell you how much I loved that night, and I’ve decided that while I’m here I’m going to do an album. And would you play drums?”

Rod: And your reaction was?

Ranjit: “Yes, of course [chuckles].” It was kind of unreal. It was almost surreal, you know. But yeah, I just jumped at it. I said, “Yeah, sure. Count me in.”

Rod: Did you feel any pressure trying to record 8 songs in only 5 days?

Ranjit: Well, I didn’t really think about it too much. I had lived with the songs for a bit. ’Cuz John came to Bombay and gave me a CD which had sketches of the songs; basically the melodies and the heads. John expected you to know the songs, and I did my homework. And if you were there, man, it was quite, quite spontaneous. We just walked in, we set up, we said hello, played for 5 minutes, and we started recording [chuckles].

We’d play it once, and I would kind of understand what John was going for. We really didn’t do more than – I guess the first day, I think was, it took longer for the set-up. But every other day, not more than 2-3 takes of each tune. Different vibe and “Okay that’s the one. Let’s mark that and let’s move on.”

It’s a jazz record. We’re not spending millions of dollars. You’re in a top studio, you want to go in, you want to capture the moment – you want to get things done. It’s not like you’re going to come there and try to go through stuff.

And it’s interesting, the “Floating Point” sessions were essentially John, me, Siva, the Indian soloists; and Louiz was the primary – Louiz was holding down changes and shit. But there were a lot of overdubs happening for the soloists. There was no bass player at the session; Hadrien dubbed later.

Rod: I thought I was up on Indian music, you know. But after hearing Niladri Kumar, Shashank, and Naveen Kumar play on “Floating Point” , I said, “Maaan, where the hell have I been? I gotta check these guys out!”

Ranjit: There are some cats here, man, who are – yeah, there is some shit going down [laughs]. Look at John: just to bring it all together and bring it all out to the west…I mean, what can I say? He’s done it again! That’s what John does, you know. He’s done it again.

Rod: I worked with Souvik on John’s last tour. And just to be around him was just…

Ranjit: Oh, he’s something else, man.

Rod: I can only imagine what it must have felt like to play with him.

Ranjit: Oh! Those five days, man, he had the energy of like an 18-year-old. Just by giving us all this space and love, he got us all fired up! All the music is – let me tell you, man. I’ve always said it: when you play music, play with people who are better than you; always. Always, always, always. You will up your game, and that’s what it’s about.

You play with people who have such standards – it really got crazy for me because after John I had to do this other gig with a bunch of guys and I was like, “What am I doing here? What am I doing here? I mean I sound like shit. What is this music?” [chuckles] It’s hard, when you get exposed to that stuff. It’s hard. So yeah, being around John was…wheew, it was a fantastic experience.

If you spend time with John, you’ll understand that you’re in the presence of a very, very deeply spiritual person. He’s definitely someone to look up to and strive to be like. During the session, John had no shame to come to me after a take, and he’d hold me and he’d say, “You have giant steps on the drum set.”

Now I’m a student, man. I don’t look at myself as any – I’m filled with humility. I’m just somebody enjoying playing this instrument and feel blessed to be in the presence of these people. I almost wept because it was so moving for me to hear my hero tell me – and validate me. More than anything else, everything I believed in, which I can’t – you know, India’s a crazy kind of place, too. There’s still not that many trap set drummers. And it’s hard to connect with shared things with people. It’s not a large drum set community like there is in the States. So when you have somebody like John validate you, it’s a big deal.

Rod: Seeing you and percussionist Anandan Sivamani play on the “Meeting Of The Minds” DVD was amazing. You guys were just killin’ it.

Ranjit: I think I was so “zoned,” man. It is hard when you play with someone you look up to. You don’t want to disappoint them…you know what I’m saying? Because we had never really “played” played together. We just jammed for 15-20 minutes that one evening, and we introduced ourselves. So when I got there, I wanted to make sure that the record sounded good. I wanted to make sure that I gave everything I had. And I wanted to make sure I lived up to whatever expectations John had of me.

Rod: John gave you guys a helluva lot of freedom on this record.

Ranjit: So much, that you can hang yourself with that much rope! And that’s dangerous, that kind of freedom. It is. It’s like, alright, here’s all this space: say something. It’s scary, it’s scary.

That was sort of an indication to me that John really wanted us to feel the moment. And it goes back to all the records that people like Miles and everyone made – that how committed are you? I think that’s all John was looking for, the commitment. Don’t pretend! Don’t play something that you think I would like to hear. Play your heart out! I want you to play, now. I wanna hear what you’re saying.

Yeah, he gave us a lot of room.

Rod: How different would it have been if bassist Hadrien Feraud had played with you at the sessions?

Ranjit: You know it’s funny. I was just talking about it the other day in the studio. I don’t know.

John was going for a really, really spontaneous combustion; that’s the only term I can think of. He wanted something that was very, very rooted in the “now,” and explosive. There was nothing – I mean we played a ballad for his wife – we’re like all over that too, man. We’re not showing “the one,” and John just loved it. Normally I would have kind of laid back. He was like, “No, no, no. I just love what you’re doing.”

So I think maybe, in one way because there was no bass player, I got to interact with John a LOT; like one-on-one. The albums got like a really, really sort of “edgy” quality to it. I mean it’s very, very – you can hear the moment. It’s very transparent. There’s no going back and trying to clean things up. It’s very, very natural.

Rod: So how did you and Sivamani arrange parts and play together without “hanging yourself”?

Ranjit: I’ve known Siva for years. It can get tricky ’cuz Siva plays percussion, but he plays a lot with sticks; it’s not just hand drumming. Siva is also a trap set player: he can play. And I think he understands the spaces and understands what I’m going for. If you listen to the track “Off The One,” you’ll see there are moments when Siva would just stop playing because he knows I’m going for something. And towards the end of “Abbaji,” I kind of stop. We had a blast.

It was very spontaneous. We weren’t trying to find just a language to speak together, we were also giving each other space ’cuz it made sense. He started playing something which made sense at that time compositionally and I didn’t need to be saying anything. I remember this one tune, I think “Raju,” I just stopped for like half a bar ’cuz I was straining to hear what was happening in the cans [chuckles]. But it was cool, it was cool. It kind of made sense musically. And John understands that – I mean, he comes from that school. It didn’t seem odd to him at all. Even Tony Williams would do that; he would just stop playing for a bit.

I think all good musicians – you listen to the song and you let the song play you. I didn’t really do anything. I just let the song play me. And I phrased it the way I understand melody and the way I would like to play a song.

There was no deep sort of intellectualizing anything. I just went with my gut on every tune, and I’d wait for John’s reaction. And in 5 days and 8 songs, all John and me did was enjoy. There was no conflict of direction or approach at all; which is great for me. ’Cuz being the first time playing with such a great musician, I was prepared for him to tell me, “Hey, maybe not like this. Play like this.” But John never, never once ordered us to be anything else but who we were.

Really, I just listened. I let the tunes play me.

Rod: I think of musicians as spiritual people, but some don’t take that approach to their music. Most listeners would say John’s music has a spiritual quality about it. Do you relate to a spiritual aspect of music?

Ranjit: Absolutely, absolutely. I mean, we’re blessed, man, in what we do. We’re very, very, very lucky. And we have to understand that if we play music, whether it’s for a living or not, we’ve been given a gift. And it’s magic; it’s nothing short of magic. To be able to imagine something in your mind and externalize it on an instrument, and bring joy not only to yourself but everyone who hears it – yes, definitely.

I basically surrendered. I’m not looking to be in control of anything – even my instrument. I seriously feel that my instrument plays me. I have to spend enough time with my instrument. The instrument looks at me as a friend. And when you spend enough time with your instrument, it shows you secrets. It shows you hidden things. It’s just like a friend: you don’t spend time, it has nothing to show you. The more time you spend with your instrument, it shows you all of its magic, and hidden things, and small things; and shares secrets with you, and tells you about stuff. That’s my approach.

I have. I have in my life; I’ve surrendered completely, man.

Rod: Kathak dancing is like a devotional in a sense. Did your mother ever talk about feeling a spiritual connection when she danced?

Ranjit: Of course, yeah. Absolutely. Plus, all the compositions that she dances to are basically hymns to the Gods, you know. So it’s all sort of revolving around religion and spirituality, both. I grew up with all that in the house. But I sort of found myself gravitating more and more towards being a Buddhist. A very close friend of mine actually exposed me to some of the beautiful teachings of Buddha.

I don’t belong to any organization, I don’t really believe in – spirituality is like the meeting place for all religions. So I’m not a great over-ritualistic guy. I think good action and good speech, that’s your religion.

Rod: You’ve been playing for awhile, now. What changes have you gone through as a musician?

Ranjit: I went through a couple of phases. For me, making the transition from being predominately a drummer to a producer in the studio – again, there were no guidelines or tech books to tell me “How do you be a good producer?” Or, “How do you make sure that everything you do is sonically excellent?”

So I did the same thing I did with drumming: I listened to the best records that were made. And the best records that I thought were being made were by people like Bruce Swedien, Al Schmitt; and all these guys. They just sounded fantastic. And I tried – again: how do I copy this sort of sonic imprint? How do I chase that thing that I’m hearing in my mind? So, it took me a long time, man.

And that’s a period where I wasn’t playing too much drums; I was doing all this other stuff. I really felt that “Well, maybe drums was my primary instrument, and maybe I was supposed to be a record producer.”

Yeah…that’s bullshit!

I can make some good records, sure. But I’ve come full circle, man. I’m back where I belong, playing drums. That’s my bag, man, you know. That’s what I love to do.

Rod: I understand you had a chance to work with Bruce Swedien?

Ranjit: Yeah, he’s Quincy Jones’ engineer. He’s a great engineer, and a very, very dear friend of mine, now. We were introduced through a common friend. He used to live up in Connecticut at that time. We met and I played him some of my stuff, and he loved it. And he said, “Anything you’re doing, I want to mix.”

Rod: Wow!!

Ranjit: That’s like a big deal.

Rod: I’ll say!

Ranjit: I’m one of maybe 15 people on this planet that he actually calls. I spoke to him the other day. I’m trying to record an album and get across so that he can mix.

Rod: He’s one of the top music engineers.

Ranjit: Oh, he’s a heavyweight, man. He’s just so – what a master.

Rod: You mentioned that you’ve been doing some teaching?

Ranjit: Yeah. There’s a bunch of kids that come to me. And really, there’s not much I can show them about the drum set. With the Internet today, if you want to learn paradiddles and slam-a-diddles; or what Mike Portnoy does and what Virgil Donati does – it’s all on the ’Net. Broken down, written out. You can ’shed and learn to play like them.

Or I can talk about a subtext of drumming: of music, really. I just sit them down and talk about the instrument. It’s great because I’ll get something out of it too. ’Cuz when you talk and you teach kids, you’re basically having to deconstruct stuff you already know; and in turn, revitalizing yourself.

It’s like the other day I told this kid who came in – and he’s got good hands this guy – and I thought what could I possibly tell him that will make his trip to me worthwhile? So I told him whenever we pick up our instrument, we have a comfort zone. We have something that we automatically gravitate to: a certain set of chops and a certain set of things that our body’s comfortable doing.

I said, “Sit down and just scat something; scat four bars of drums to me. Just say it, just say what’s in your mind right now.” And I said, “The minute you finish scatting, just play; play exactly what you just scatted.”

He just sat back and he said, “Wow, man. That’s kind of tricky.” And I said, “Yeeeah, that’s the idea [chuckles]. That’s to make sure that for the next half-hour you’re not going to bother me. You’re gonna be stuck in there, chasing that four bars down.”

What I’m trying to say is that if you spend enough time with your instrument then what you think, what you improvise, can be executed in real-time. You don’t have to rely on stuff that you’re familiar with. As a part of an ever expanding vocabulary, it’s possible to play the moment so exactly, that you think in real-time and you play exactly that.

So it’s really kind of an informal place I have; it’s not regular classes. Kids just roll up. I take an hour out during lunch, we sit, we talk, we play some drums. They show me stuff, too. A lot of these young kids they’re into JoJo Mayer. You know JoJo?

Rod: Uh, no.

Ranjit: Awww, GREAT drummer, man. I think he’s Austrian or German. Aww, killer!

Rod: Does he play with a group?

Ranjit: He has a band of his own called Nerve.

Rod: Naaw, I haven’t heard him.

Ranjit: Aw, man. You will love him. He is a KILLER, this guy! I love his playing. He’s one of the few cats on the scene recently I’ve heard who – yeah, I like him! I like what he’s doing. And he’s a great, great technician; obviously worked very hard.

And so, yeah you know. It’s an informal place, and I enjoy it. I enjoy it.

Rod: Is your daughter Mallika showing any musical talent?

Ranjit: She learning guitar, man [chuckles]. You know, I kept exposing her to stuff. I sent her to learn dance from my mother; she’s not into that. I started her on Carnatic vocals; kind of got into it, but naaaw. She’s like a “rock chick.” Yeah, she’s like a rocker, man. She hears all these bands like Green Day and shit and gets up – she’s learning guitar; and she can sing, man. And she’s got good time. I took her to the studio and I showed her a couple of grooves. She played it straight up, and that really disinterested her, and split.

Rod: Hey, maybe you guys will do duets like John and Billy in the MO days?

Ranjit: I tell you. No, I think she’s got something. And I’m just trying to expose her to everything, and then she’ll choose. She’ll choose.

Rod: That’s cool.

Ranjit: Yeah.

Rod: One of the things that I love about your playing is your cymbal work. You have a wonderful feel. I can’t really describe it. You know we guitar players are just frustrated drummers.

Ranjit: I’m a frustrated guitar player [chuckles]. I wish I could play the guitar, man

Rod: The way you place your hits and your ride; I just felt “Man, that’s the shit!” I really love what you were doing.

Ranjit: It’s like an extension, actually, of the way I heard Elvin Jones play. That whole “forward motion” thing. Constantly propelling, moving ahead. I mean, Elvin had that. For me he’s – he was something, man. The multi-timbre tabla players, they play that same forward propelling kind of thing. Zakir bhai does it.

You know the funny thing is, when I’m hearing drums in my head, the whole line between India and the drum set gets blurred. Because I’m hearing the same thing in my head. If I’m hearing like an up-tempo drum thing like [sings] boom, dah, chinga-chinga-chinga, boom, dah, I’m actually hearing in my head [sings in konnokol] da da taka takita takita takita da. It’s the same; it’s really the same, man. I play it right on the drum set.

Rod: In my review for “Floating Point” , I say that your rhythms, along with Sivamani, are “propulsive.”

Ranjit: Yeah, that’s true. It really is.

Rod: Just your whole playing, man. I really want you to know just how much I enjoy listening to you.

Ranjit: I appreciate that.

Rod: I see that you use two snares in your drum set. Is that for tonal reasons?

Ranjit: It’s more a tonal thing. For John’s session I used a sort of Jungle kit. The dimensions are really small; the bass drums like a 16-inch. Not even an 18-inch, a 16-inch. And John just loved it! John looked at the kit and he said, “Wow, do you like jungle music?” [chuckles]. I said, “I love jungle.” He said, “I love jungle, man. I think it’s like the new kind of jazz.” I said, “Well, we’re in agreement there.”

The whole idea of having the 10-inch snare on one side and the 12-inch snare as my main is I have two sorts of tonalities happening in the kit, basically. And I have two rides: I play one ride for the right hand, the other darker ride for the main kit and the snare. And when I switch over to the 10-inch piccolo, I have a brighter sort of ride. So you hear two sets of tonalities happening on the album.

Rod: Didn’t Tony Williams play a small bass drum?

Ranjit: Yeah. He played like an 18. He played like an 18; yeah, yeah. There’s something about that. I like it.

Rod: My promo of “Floating Point” was transferred from mp3’s, so you don’t hear the full resonance of the drums. But the drums sound good on mp3, so I’d imagine they’d sound awesome on the CD.

Ranjit: Well in fact, I find from the mixes that the bass drum has been kind of toned down a bit. The 16-inch? Oh, the 16-inch in my rough mixes is like an animal! It sounds huge. I was kind of surprised ’cuz that’s actually the first major recording I did with that kit. I was surprised at how big it sounded. In fact, Steve Smith hooked me up with that kit. I was touring the U.S. with Zakir bhai and we needed a compact kit to carry around. So Steve – living out on the west coast at that time – he hooked me up with that drum set.

Rod: John has a reputation for playing with awesome drummers: Cobham, Narada, Chambers, Zakir Hussain to name a few. Do you feel like you’re a “John Drummer” now?

Ranjit: Well, it feels good to be in this company, man. I think there is significance, if like you said, if John chooses you as a drummer. There’s some significance attached ’cuz he has such good taste. And I think he connects with a particular kind of drumming.

I think – let me tell you really what I got out of this whole experience. One is: I feel blessed to have played with John McLaughlin. Two: I remember telling John when we were wrapping. I said, “John, you spoiled me now. You came and you played with me for five days, you make an album, and now you leave…that’s fucked up [laughs]. You know that’s not fair.” He goes, “Ooooh, don’t worry, don’t worry. I’ll be back.”

I know we’re going to play again in the future, I know that. But what it did for me was – it was almost like your guru giving you a pat on the back and saying, “Say, you’re okay. Go. Go. Go into the world, go do your thing.” It’s also significant because that whole process from being a drummer, to record producer – and coming out of it, I’m back into playing drums. Now I am choosing to go and only play the drum set as a way of expressing myself, and also as a way of feeding my family. And that’s a big decision.

Record producers, let me tell you, make more money. There’s more money to be made in doing that, but that’s not what interests me. What interests me is that something I started doing a long time back is what I really need to do for the rest of my life.

Rod: So that feeling of realizing “your calling” is more solidified, now?

Ranjit: It’s more solidified. It’s been coming for awhile. Zakir bhai’s been exposing me and pushing me. Zakir bhai and Terry Bozzio came to see me play a gig here in Bombay. And it was a good night; the band was smoking. Zakir bhai took us out to dinner and he says, “Man, all the time you’ve put in, I’d love to see you more out there than just here. You gotta get out, man.”

But it’s been coming for awhile. John’s thing, it was just like “boom,” this is it . It doesn’t get any more real than this; it does not. So it’s very significant in my life from that perspective. That validation has helped me make things clearer for me – for my future. And I think that’s huge compared to anything else. To actually know where you want to go; what you want to do for the rest of your life.

Rod: So how would you describe your own music, your own direction?

Ranjit: It’s um…well what can I say? Sort of modern music with – I’m trying to find a very…it’s like what John is doing. How do you take such a deep culture like Indian music, yet make it easily accessible to everyone? So I have slightly more, how do you say – it’s not so much “jazz” jazz, but it’s also a strong influence of the late Joe Zawinul. ’Cuz he was another one of my heroes. I thought Joe was another prophet, you know.

Along with John, Joe has shown us how to make egoless music. Music with no ego, man. And Joe did that. He said, “I wanna make jazz that people can dance to.” Joe Z. was one of the most incredible musicians, ever. He took everything he learned from all the greats like Miles and distilled it into such a celebratory music. So I think he’s a big influence on my writing, as well.

Another big influence on my writing is because I worked for so long scoring films and cinema, there’s a certain cinematic element that I do as well. It’s a little “wider.” Some of it is kind of film score “live” on stage.

So those are things I’m gunning for. It just so happens that these are things that I feel for, I truly love doing. I get excited by playing and composing this stuff. And in turn, it’s also new territory, musically. We have to be in some sort of position to contribute to this vast pool of music in this world. There’s no point in just being a trio or quartet that’s gonna go out and say some stuff that’s already been done. We have to put a spin on things. We have to reinvent something in our lifetime so that we can contribute: if we get to do it at all.

So it’s hard to describe the music – it’s all these things. It’s all the stuff I’ve grown up with. I have to put my DNA on it and put it out.

Rod: I saw a clip of you on YouTube playing in a trio.

Ranjit: With Amit Heri. Amit is a very, very close friend of mine. We going to be playing – we’re recording an album, actually. We’re gonna record our music with a Carnatic musician: he’s an incredible virtuoso this guy. He’s just a scary, scary musician. He sings, plays mridangam, flute; and also plays keyboards – but – like a Carnatic instrument. And he’s fighting the Carnatic Music Academy to accept that keyboard playing as part of a Carnatic instrument. If you close your eyes and hear the guy playing, it sounds like a vina, man.

Rod: Oh wow.

Ranjit: This guy, he will scare you when he explodes on the scene. This guy’s a monster.

Rod: What’s his name?

Ranjit: His name is Pallakad Sriram. And he’s like a virtuoso, man. So him, Amit, me; and I have a bass player friend of mine from Belgium who plays with Dominic Miller: Sting’s guitar player, Dominic. He’s a Belgium friend of mine. He’s an old, old, old friend. Me, him, and Charlie Mariano played a long time back. His name is Nicolas Fiszman, and we’ve played on-and-off together; but he’s the bass player in the band. So we’re getting ready to record, and I’d like to put that out, and take this riding on the road, man.

Rod: What other future projects do you have planned?

Ranjit: Well I’m doing this album with Amit and Sriram. There’s one album – I really want to record with a great sarangi here called Ustad Sultan Khan. He’s an exponent of this instrument called the sarangi which is north Indian; very few people play it anymore.

Rod: Yeah, it’s a bowed string instrument.

Ranjit: Yeah, yeah. I want to do something with him. That’s a more sort of electronic – it’s an interesting band which I’m trying to do. The band is called Ohm Transport. There’s a DJ, Sultan Khan, there’s myself, guitar and bass; and it’s quite, quite interesting [chuckles]. But it’s going to take a little work to get it all to happen. So that’s something that I’m trying to work on.

Rod: It sounds as if you’re still pushing boundaries.

Ranjit: Yeah, I want to. You know when you start really paying attention to music, you find this meeting point for every instrument in everything. There’s a commonality. There’s a place where all cultures and everything meet. And I think all the great musicians like John can see it clearly. You know? They can see that place clearly. If we get even a glimpse of it, once you get a taste of that, you start chasing that. It’s very, very addictive.

Rod: Do you feel you still have to break down barriers between east and west to get to that point?

Ranjit: Actually, I’m trying to get – it’s really, really bizarre, man. I’m trying to get people in India more tuned into their own music.

Rod: Really??

Ranjit: Yeah. I mean, I’m talking about young western audiences, contemporary musicians. None of the guitar players and bass players here pay attention to Indian rhythms and Indian stuff. And I’ve been telling them for years, “Listen, man. The future of music depends on all our cultures integrating.”

So really, the hard part is – like the other guitar player that I work with Amit Heri, whose clip you saw on YouTube, he’s hip to the Indian thing. I don’t have to convince him, and I don’t have to teach him anything. He’s a master in his own right. Now the other kids, like the DJ…I mean, [chuckles] it’s not like I’m trying to make some hip-hop band. It’s gonna have some shit going on, and the DJ’s got to be tuned into that.

So, that’s a bit of a grind, but I think it’s gonna be interesting.

Rod: So how do you see yourself in – I don’t know, let’s pick a number – 10 years from now, where would you like to be?

Ranjit: I’d just like to be – what can I say, man? I mean, making music, playing, building bridges between India and the rest of the world. Play with more fantastic musicians, you know.

Rod: Do you have a dream list of musicians – not necessarily of the west, but musicians in general – that you’d like to work with?

Ranjit: I haven’t really thought about it that much, you know. I think I’m a bit of a uh, how you say, “outsider.” I like to do my own thing mostly, as a leader. Really, most of the musicians that I want to play with are from south India. They’re all incredible people, man. I have very strong compositional ideas and direction that I want to pursue. Like I had this dream idea for a band with an Indian horn section.

Rod: Wow!

Ranjit: The horn section is all Indian Carnatic players.

Rod: Yeah! Now that’s something you wouldn’t normally think of [chuckles].

Ranjit: Yeah, man. I’m telling you. That excites me, that excites me. To have three alto saxophone players, or two alto saxophone and one – are you aware of this instrument from the south called nagaswaram?

Rod: Yeah. It’s a double reed horn.

Ranjit: Like one nagaswaram player, two sax players; playing like unison parts and harmony parts. Man, that is the shit!

These are some of the things I’m gonna be chasing. I’m excited. I have to do music that I’m excited about. I’m not a gun-for-hire. I don’t really think of myself as a “drummer” drummer. I’m a musician whose primary instrument is the drum set. But I’ve got something to say compositionally and conceptionally; and I want to realize that. That’s really what I want to do.

Rod: Well, this is the “open mic” part of the interview. Is there anything that you want to say or talk about?

Ranjit: One interesting thing during John’s session – and I don’t mean to be controversial – but all my Indian musician brothers… I think it was the second day – it was the day Nildari was there playing zitar. We were all recording. But when John was not there, when John goes away, we don’t CONNECT that much as Indian musicians. And I said, “Listen, it took John to get all of us in one room. So when John goes away, let’s not be strangers, man.”

I feel we need to have some of that spirit creep into the contemporary Indian music scene. That “searching spirit”: the spirit to need to interact with those worthwhile. Art cannot exist in a vacuum, man. It’s not possible. This is a dialogue; these are conversations that we hear on tape. These are conversations, and it’s not a monologue, man.

So there’s a lot of stuff happening here, I just want it to explode. I want people to connect. Something sonically has to come out of this dialogue. The more we hang, the more we play, it’s gonna give rise to “A Sound”, you know. I hope it happens. [pauses] That’s it.

Rod: Ranjit, I can’t thank you enough. I really appreciate you taking the time to talk. I had a great time, and I hope you did as well.

Ranjit: It was a blast for me too, man.

Rod: You’re very gracious, and you’re a helluva drummer. I just love what you’re doin’, and I hope we get to hear more of it.

Ranjit: Inshallah.

Latest album

Latest NEWS

SUBSCRIBE

Please Subscribe your mail to get notification from AbstractLogix.

Facebook-f

Twitter

Instagram

Youtube

Copyright © 2021 ABSTRACT LOGIX

Facebook-f

Twitter

Instagram

Youtube

Copyright © 2021 ABSTRACT LOGIX